If you collect Arts & Crafts pottery, you probably already know Grueby, Marblehead, and Teco. But Van Briggle belongs in that conversation too — and it offers something the others don’t.

Van Briggle sits at the exact intersection of Arts & Crafts and Art Nouveau. It has the matte glazes, the nature motifs, the handcraftsmanship, and the philosophical rejection of industrial production that define the Arts & Crafts movement. But it also has the flowing sculptural forms, the human figures, and the dramatic organic lines of Art Nouveau. This dual identity makes it one of the most interesting crossover collecting areas in American decorative arts.

The Movement in Brief

The Arts and Crafts movement started in Britain as a reaction against industrialization. John Ruskin and William Morris argued that mechanized production was dehumanizing — that a healthy society needed independent workers who designed and made the things they created. Morris became the movement’s figurehead, advocating for honesty of materials, simplicity of form, nature as inspiration, and the unity of all arts within the decoration of the home.

The movement crossed the Atlantic in the 1890s. The Boston Society of Arts and Crafts was founded in June 1897 — the first in America. The Chicago Arts and Crafts Society followed in October, with Frank Lloyd Wright as a founding member. Gustav Stickley launched The Craftsman magazine in 1901, dedicating the first two issues to Morris and Ruskin. By 1900-1916, the movement was in full bloom in America.

American practitioners adapted Morris’s ideas to their own context. They drew on indigenous materials and motifs, embraced a more capitalist approach than Morris’s socialism, and were generally more willing to use machinery alongside handwork. But the core values held: honesty, simplicity, nature, and the dignity of craft.

Where Van Briggle Fits

Artus Van Briggle established his pottery in 1901, right in the middle of the Arts & Crafts flowering. The official Van Briggle website explicitly positions the pottery within the movement: Artus “established his pottery during the Arts and Crafts movement, a time when many artists and craftsmen were creating their works in reaction to the mass production of the industrial revolution.”

Here’s what makes Van Briggle an Arts & Crafts pottery:

Matte glazes. The matte finish was central to the Arts & Crafts aesthetic — it rejected the glossy, ornate surfaces of Victorian-era ceramics in favor of subdued, honest surfaces. Van Briggle’s matte glazes were pioneering in America. Grueby had popularized the matte green glaze, and Hampshire and Teco followed suit, but Van Briggle brought a broader palette — turquoise, deep terra cotta red, tobacco yellow, mulberry, Persian rose, and dozens of blues and greens.

Nature motifs. As the official site puts it, “The subject of Van Briggle is, essentially, nature.” Hundreds of designs feature flowers, animals, and human subjects drawn from the natural world. This is pure Arts & Crafts territory.

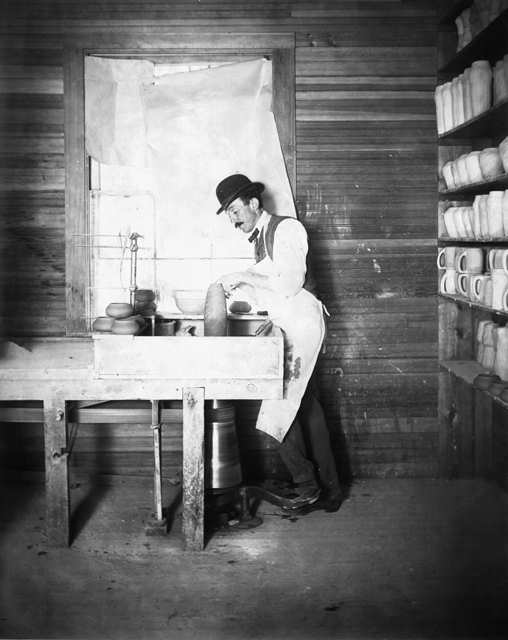

Handcraftsmanship. Though molds were used for consistency, production was limited in number and each piece was carefully retouched or painted by hand. The decorators carved thrown earthenware vases with motifs individually, then submerged them in prepared vats of glaze. The pottery maintained this commitment throughout its history.

Philosophy of accessible art. Van Briggle’s stated goal was “to provide society with a counterpoint of artistry and hand craftsmanship” in an era dominated by technology. This echoes Morris’s vision of making beautiful things available to ordinary people — one of the movement’s defining tensions.

The building itself. The Van Briggle Memorial Pottery Building, designed by Nicolaas van den Arend in 1907-1908, was itself an Arts & Crafts statement. The National Register nomination specifically notes that “these decorative components reflect the Arts and Crafts disdain of mass-produced goods and preference for handcraftsmanship, while the brick walls and stone foundation display a desired solidity and connection to nature.”

But Also Art Nouveau

Where Van Briggle goes beyond a typical Arts & Crafts pottery is in its sculptural ambition. The Lorelei vase — a mermaid wrapped around the vessel — is pure Art Nouveau. So is the Despondency, a male figure folded over the rim in anguish. The Lady of the Lily. The Toast Cup with its mermaid holding a fish. These flowing, figural forms are characteristic of Art Nouveau’s curvilinear drama, not the rectilinear simplicity typical of Arts & Crafts.

This isn’t a contradiction — the two movements overlapped significantly, especially in American pottery. Arts & Crafts focused on the method of production (handcraft above all), while Art Nouveau was more about design innovation and expression. Van Briggle met both criteria simultaneously.

How Van Briggle Compares to Other Arts & Crafts Potteries

If you’re an Arts & Crafts collector, here’s how Van Briggle stacks up against the names you already know:

Grueby (Boston, 1894-1920) — Arguably the most important Arts & Crafts pottery. The signature organic matte green glaze became the standard that everyone else chased. Commands the highest prices. Van Briggle shares the matte aesthetic but offers a wider color palette and more sculptural forms. Generally more accessible in price.

Teco (Illinois, 1899-1922) — Matte green pottery that defined the Prairie School aesthetic. Geometric, architectural forms that complement Frank Lloyd Wright interiors. Van Briggle is more organic and flowing where Teco is angular and architectural. Both used molds.

Marblehead (Massachusetts, 1904-1936) — Simple forms, pleasing matte glazes, hand-thrown and individually decorated. More subdued and rectilinear than Van Briggle. Both appeal to collectors building Arts & Crafts interiors.

Newcomb College (New Orleans, 1894-1940) — All pieces thrown and decorated by hand, no two alike. Strong Art Nouveau style, often with local landscape motifs. Like Van Briggle, it blends Arts & Crafts values with Art Nouveau aesthetics. Best Newcomb pieces can be worth tens of thousands.

Rookwood (Cincinnati, 1880-1967) — Where Artus Van Briggle trained. Rookwood’s strength was painterly surface decoration; Van Briggle’s was sculptural form. Rookwood has been collected longer, with prices that have peaked and fallen.

Why Arts & Crafts Collectors Should Look at Van Briggle

A few practical reasons:

Price. Van Briggle remains more accessibly priced than Grueby or the best Newcomb. Other pottery names like Roseville, Weller, and McCoy have been collected longer and seen their prices peak and fall. Van Briggle offers a more cost-effective collecting opportunity at most price points.

Decorative versatility. Arts & Crafts collectors routinely mention Van Briggle alongside Grueby and Teco as natural complements for Mission and Craftsman interiors. The matte glazes and nature motifs are completely at home in an Arts & Crafts setting.

Museum pedigree. Pieces in permanent collections at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian, the V&A in London, and museums across Colorado. Multiple gold medals from the Paris Salon. Honored at the American Arts and Crafts Exhibition in Boston.

Range. With over a century of production, there’s a Van Briggle piece at virtually every price point. Early dated pieces (1901-1912) with original matte glazes command the highest values, but collectors can build meaningful collections at far more modest budgets.

The dual appeal. Because Van Briggle bridges Arts & Crafts and Art Nouveau, the collector base is broader. A Lorelei vase looks as natural in an Art Nouveau display as it does alongside Stickley furniture.

For more on dating and identifying Van Briggle pieces, see our Markings & Identification Guide. To see early pieces up close, visit our Gallery.

Recommended Books

For collectors exploring the Arts & Crafts pottery world:

- Van Briggle: The Collector’s Encyclopedia of Van Briggle Art Pottery — the essential identification and value guide with 800+ pieces.

- Grueby: The Ceramics of William H. Grueby — the definitive study of the most important Arts & Crafts pottery.

- Newcomb: Newcomb Pottery: An Enterprise for Southern Women — the story of the unique New Orleans pottery.

- Weller: Collector’s Encyclopedia of Weller Pottery — comprehensive guide to one of the most collected American potteries.

- Roseville: Introducing Roseville Pottery — a Schiffer collector’s guide to this widely collected brand.

- The Movement: The Arts and Crafts Movement provides excellent historical context, and Craftsman Homes by Gustav Stickley shows how pottery fit into the complete Arts & Crafts interior.

- Broad overview: Arts and Crafts: Pottery and Ceramics covers the full ceramic tradition of the movement.